by Dr. Hy Gia Park and Dr. Charles Park

Depression is a disease that affects more than just the brain. Many with depressive illnesses have signs of premature aging. They have an earlier onset and a significantly higher rate of coronary artery disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. Osteoporosis, or bone mass loss most frequently seen in the elderly, is seen in pre-menopausal women who have depression. The premature aging and death of individuals with depressive disorders is a result of many normal bodily functions, originally designed to protect and enhance the body’s response to stress, having gone awry.

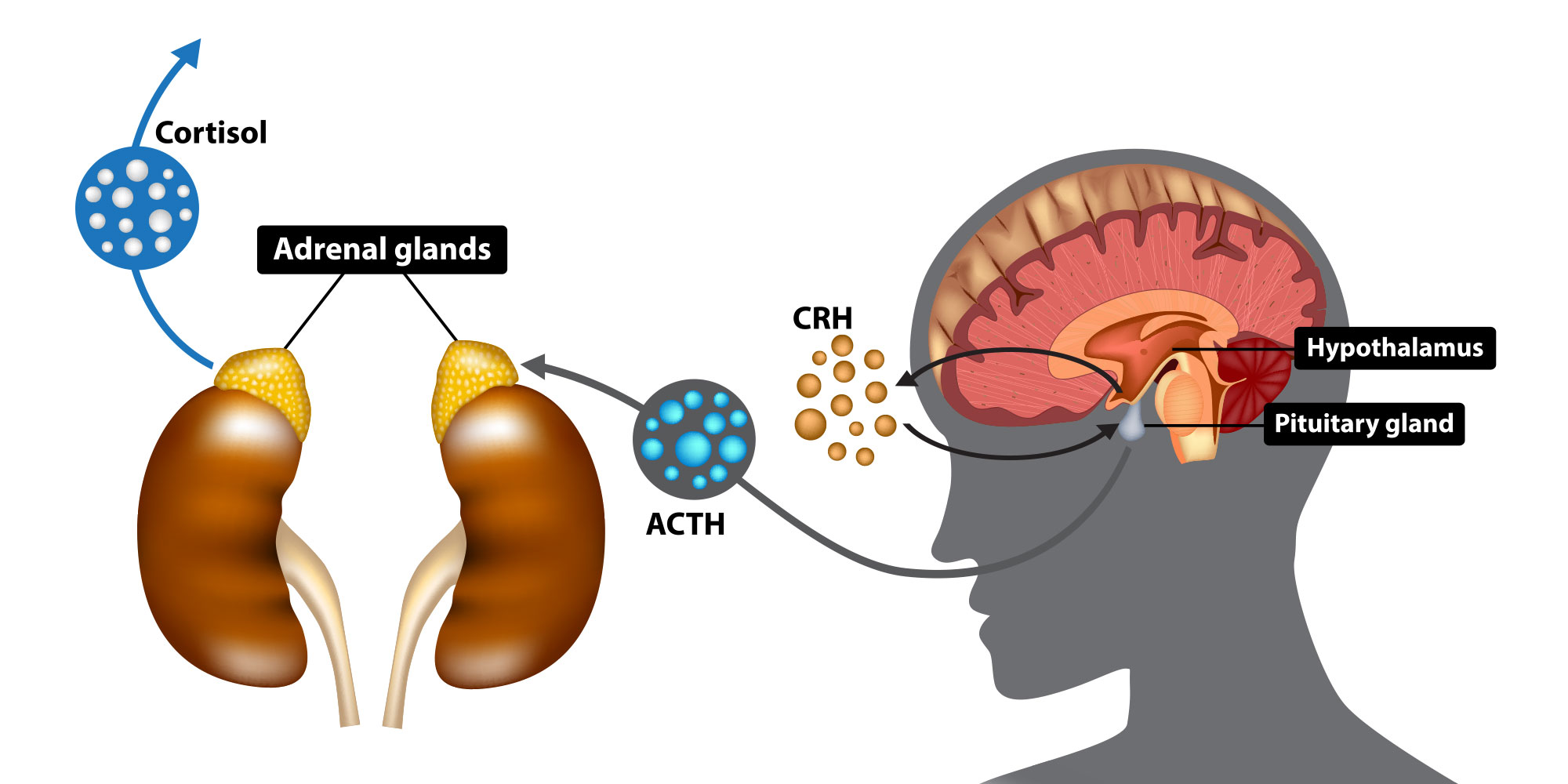

In a previous article, we discussed how clinical depression is a disease caused by a prolonged stress response. The brain changes in response to environmental and relationship stress by altering its chemical environment and either activates or slows down the function of various brain areas. For example, the brain may reduce dopamine activity and prefrontal cortex activity which decreases the need to sleep, rest, eat or have sex while dealing with stress. The brain also controls the rest of the body through chemical output from a key chemical factory called the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, especially via a hormone called corticotropin releasing factor (CRH or CRF). When the prefrontal cortex (PFA), the front part of the brain implicated in planning complex cognitive behavior, personality expression, decision making, and moderating social behavior, is not stressed and therefore more active it may suppress corticotropin releasing hormone CRH/HPA axis activity. However, during stress, PFC activity may be suppressed which then leads to increased activity of the HPA axis and release of CRH. CRH through a cascade of events and an intermediary hormone produced in the pituitary called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) eventually leads to the release of various hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol by the adrenal glands. CRH also prevents thyroid, sex and growth hormones from being produced in order to preserve the body’s resources so it can respond to the immediate stressful situation.

Adrenaline and cortisol prepare the body to respond to fight-or-flight situations by promoting anxiety and fear-related behaviors and inhibiting appetite and sleep. They effect the function of the circulatory, immune, nervous, and endocrine systems as it anticipates possible blood loss, tissue damage, and infection from injury sustained during a physical altercation or during escape. Adrenaline helps to boost the body’s energy supply and increases both blood pressure and heart rate. Cortisol is the primary stress hormone that regulates metabolism, the immune response and how the body responds to stress. It promotes insulin resistance so that more glucose (fuel that the body runs on) is readily available in the bloodstream to be directed to the brain and other stressed body sites, as they all require extra energy during the stress. At the same time, it curbs body functions that are deemed non-essential or even detrimental to survival, such as growth, reproduction, and digestion. Cortisol leads to a prothrombotic state by increasing the blood’s ability to form clots. Finally, cortisol causes the immune system to release proteins called cytokines, which mediate and regulate inflammation, immunity, and the process in which blood cells are manufactured in the body. Cytokines are particularly powerful reinforcers of this stress response cascade because when their levels in the blood drop, the entire stress response system reactivates again, beginning with increasing activity of the CRH/HPA axis, then the sympathetic nervous system, which them leads to insulin resistance, increasing inflammation and blood clotting, so on and so forth. While all these effects are necessary and useful in short-term stress situations, these processes become quite detrimental to the body as a whole when they do not turn off. We will cover the adverse effects of the body’s stress response when it is prolonged, which is what happens in clinical depression, in next month’s article.

Reference:

PW Gold; “The organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in depressive illness;” Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 32–47; doi:10.1038/mp.2014.163