Author: Arahant Admin

Mile High Sports Magazine – Guest Article #5 – Dec. 2019

by Dr. Hy Gia Park and Dr. Charles Park

Depression is a disease that affects more than just the brain. Many with depressive illnesses have signs of premature aging. They have an earlier onset and a significantly higher rate of coronary artery disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. Osteoporosis, or bone mass loss most frequently seen in the elderly, is seen in pre-menopausal women who have depression. The premature aging and death of individuals with depressive disorders is a result of many normal bodily functions, originally designed to protect and enhance the body’s response to stress, having gone awry.

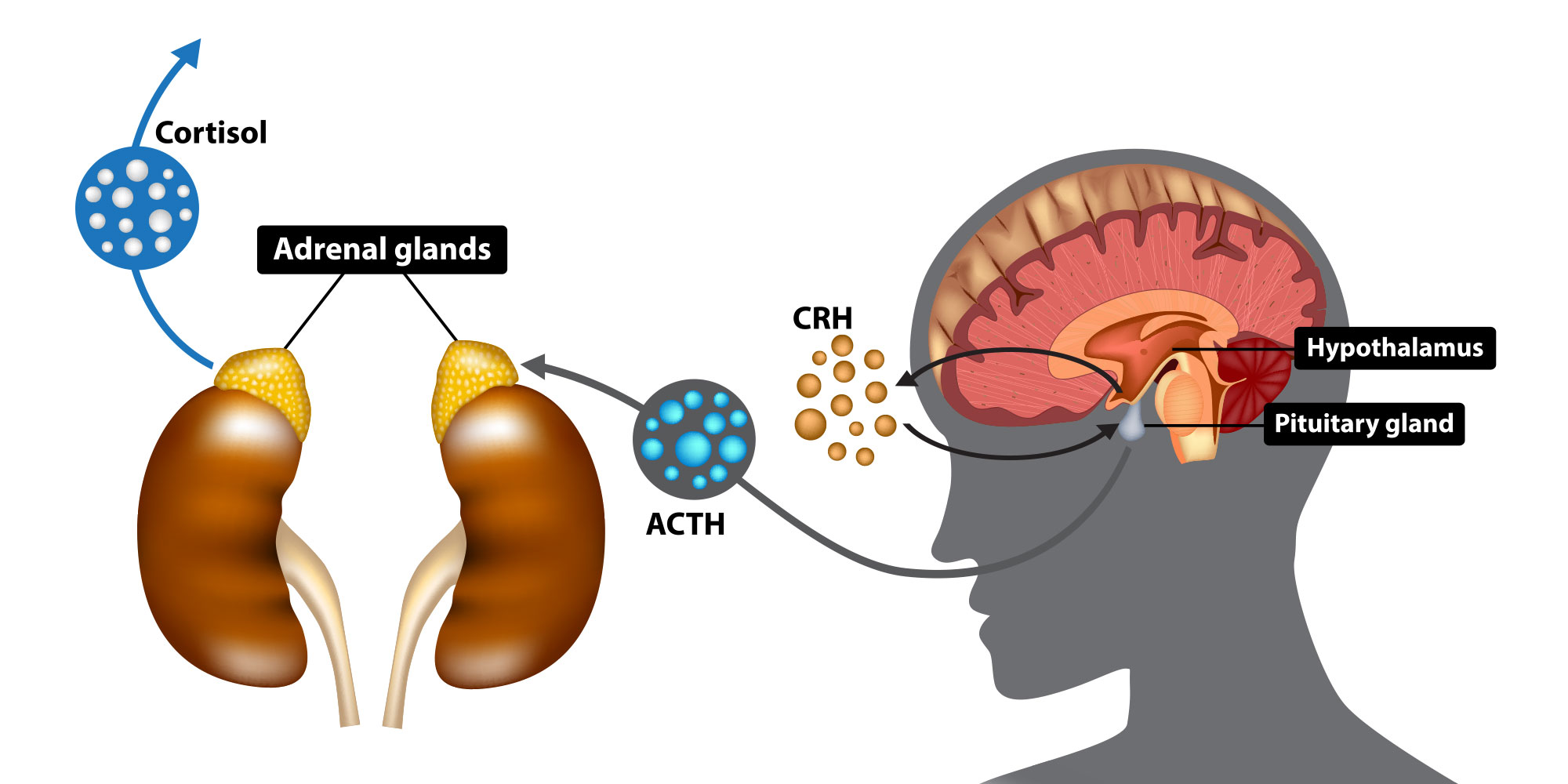

In a previous article, we discussed how clinical depression is a disease caused by a prolonged stress response. The brain changes in response to environmental and relationship stress by altering its chemical environment and either activates or slows down the function of various brain areas. For example, the brain may reduce dopamine activity and prefrontal cortex activity which decreases the need to sleep, rest, eat or have sex while dealing with stress. The brain also controls the rest of the body through chemical output from a key chemical factory called the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, especially via a hormone called corticotropin releasing factor (CRH or CRF). When the prefrontal cortex (PFA), the front part of the brain implicated in planning complex cognitive behavior, personality expression, decision making, and moderating social behavior, is not stressed and therefore more active it may suppress corticotropin releasing hormone CRH/HPA axis activity. However, during stress, PFC activity may be suppressed which then leads to increased activity of the HPA axis and release of CRH. CRH through a cascade of events and an intermediary hormone produced in the pituitary called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) eventually leads to the release of various hormones, including adrenaline and cortisol by the adrenal glands. CRH also prevents thyroid, sex and growth hormones from being produced in order to preserve the body’s resources so it can respond to the immediate stressful situation.

Adrenaline and cortisol prepare the body to respond to fight-or-flight situations by promoting anxiety and fear-related behaviors and inhibiting appetite and sleep. They effect the function of the circulatory, immune, nervous, and endocrine systems as it anticipates possible blood loss, tissue damage, and infection from injury sustained during a physical altercation or during escape. Adrenaline helps to boost the body’s energy supply and increases both blood pressure and heart rate. Cortisol is the primary stress hormone that regulates metabolism, the immune response and how the body responds to stress. It promotes insulin resistance so that more glucose (fuel that the body runs on) is readily available in the bloodstream to be directed to the brain and other stressed body sites, as they all require extra energy during the stress. At the same time, it curbs body functions that are deemed non-essential or even detrimental to survival, such as growth, reproduction, and digestion. Cortisol leads to a prothrombotic state by increasing the blood’s ability to form clots. Finally, cortisol causes the immune system to release proteins called cytokines, which mediate and regulate inflammation, immunity, and the process in which blood cells are manufactured in the body. Cytokines are particularly powerful reinforcers of this stress response cascade because when their levels in the blood drop, the entire stress response system reactivates again, beginning with increasing activity of the CRH/HPA axis, then the sympathetic nervous system, which them leads to insulin resistance, increasing inflammation and blood clotting, so on and so forth. While all these effects are necessary and useful in short-term stress situations, these processes become quite detrimental to the body as a whole when they do not turn off. We will cover the adverse effects of the body’s stress response when it is prolonged, which is what happens in clinical depression, in next month’s article.

Reference:

PW Gold; “The organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in depressive illness;” Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 32–47; doi:10.1038/mp.2014.163

Mile High Sports Magazine – Guest Article #4 – Nov. 2019

by Dr. Hy Gia Park and Dr. Charles Park

Isn’t cannabis approved for mental health conditions like depression?

Cannabis and related products don’t have FDA-approval for use in psychiatry. Pooled data found cannabis usage was highest in people with depression and anxiety. Despite any subjective, temporary symptom relief, cannabis use1:

- Worsened symptoms of depression and PTSD.

- Contributed to that start of bipolar and PTSD and worsening their disease course.

- Worsened severity, persistence, and frequency of manic and psychotic episodes in bipolar.

How can I use cannabis safely?

The National Academy of Medicine concluded there “is insufficient information on the health implications of cannabis use” and that “no accepted standards exist to help guide individuals as they make choices regarding if, when, where, and how to use cannabis safely and, in regard to therapeutic uses, effectively.” The Academy also expressed public health concerns about adolescents, pregnant women, and those with mental health conditions using cannabis.2

Alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use were independently associated with job loss in the short- term, with higher risks associated with higher dosages. Even moderate use, defined as 2-4 alcoholic drinks monthly, 1/2 to 1 pack of cigarettes daily, or cannabis use once monthly, was associated with job loss, regardless of job grade, age, gender, income, and education level.3

Doesn’t everyone use cannabis?

Cannabis continues to be the most widely used drug worldwide with 3.8% of the world’s population using compared to 0.2% for cocaine and 0.2% for opiates. Use is highest in North America (13.8%) followed by Oceania (10.9%) and West and Central Africa (10%).4 In 2108 in the US, 15% of 12-17-year-olds (13.9% of 8th graders, 32.6% of 10th graders, and 43.6% of 12th graders) 5, 15.5% of 18-25-year-olds, and 47.8% of those 26 and older have used cannabis in their lifetime. 1 in 17 of college students use cannabis daily compared to 1 in 9 for their non-college peers.6

Is cannabis really that bad?

Scientific evidence clearly indicates that cannabis use leads to both short and long-term adverse effects. Short-term effects include, impairment of learning and attention, retention of information, short-term memory, coordination, and judgment, all of which can lead to injuries, car accidents, and risky sexual behaviors. Long-term and heavy use leads to addiction (9% in adult users, 17% in teenagers, and up to 25-50% if use is daily and began as a teen), addiction to other substances, impaired cognition, altered brain development, chronic bronchitis, higher risk of paranoia and schizophrenia, and diminished lifetime earning potential, educational achievement, and life satisfaction. 7

In Colorado between 2000-2015, marijuana-related hospitalizations and emergency room (ER) visits increased by 116%. Cannabis-positive drug tests have increased for teens and young adults with the majority requiring psychiatric evaluations. The prevalence of mental illnesses was 5-times higher for ER visits.8

Young people don’t need to worry about cannabis until they’re older, right?

Cannabis exposure during brain development, beginning in the prenatal period and ending in our early twenties, is a huge public health concern. A growing brain is more susceptible than a mature brain to environmental toxins, such as tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary active ingredient in cannabis. THC exposure in adolescence can alter the sensitivity of the brain’s reward system to other drugs, like alcohol, opioids, etc. and prenatal exposure adversely changes brain cells by affecting their function, and how they communicate and work with one other cells.7

I don’t use that much. Will my health really improve if I give it up?

Studies have shown that long-term exposure to THC strengthens the emotional and reactive parts of your brain while weakening the rationale and self-control parts of the brain. Scientist believe the effects of THC on these parts of the brain likely contribute to the cognitive and psychiatric dysfunction discussed earlier.9

Airway inflammation and bronchitis are largely reversible when cannabis usage stops. Cough, mucus production, and wheezing reduce to levels seen in non-cannabis users.10

Aren’t CBD-only products okay?

Cannabidiols (CBD) has become quite ubiquitous. CBD is only FDA-approved in children for specific forms of epilepsy as Epidiolex and in adults for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting as Cesamet. The therapeutic potential of CBD in treating mental health conditions from anxiety, depression, bipolar to PTSD has not been well‐studied.1 The FDA recently published a consumer update warning Americans that CBD can cause liver toxicity and are being marketed with unproven medical claims.11

While studies have shown anti-anxiety, anti-seizure, and anti-psychotic properties of CBD, the consensus in the scientific and medical community is that we need a better understanding of:

- the human endocannabinoid system, which keeps our internal body environment stable and optimal.

- The properties of CBD, including safety, applications, and precise dosing for treating psychiatric conditions with more clinical trials.12

References:

- Botsford, S. L., Yang, S. and George, T. P. (2019), Cannabis and Cannabinoids in Mood and Anxiety Disorders: Impact on Illness Onset and Course, and Assessment of Therapeutic Potential. Am J Addict. doi:10.1111/ajad.12963

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24625.

- Airagnes G, Lemogne C, Meneton P, Plessz M, Goldberg M, Hoertel N, et al. (2019) Alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use are associated with job loss at follow-up: Findings from the CONSTANCES cohort. PLoS ONE 14(9): e0222361. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222361

- World Health Organization https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/facts/cannabis/en/

- https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/marijuana

- https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/drug-alcohol-use-in-college-age-adults-in-2018

- Volkow, N. D., Baler, R. D., Compton, W. M., & Weiss, S. R. (2014). Adverse health effects of marijuana use. The New England journal of medicine, 370(23), 2219–2227. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1402309

- Roberts B. A. (2019). Legalized Cannabis in Colorado Emergency Departments: A Cautionary Review of Negative Health and Safety Effects. The western journal of emergency medicine, 20(4), 557–572. doi:10.5811/westjem.2019.4.39935

- Hwang E-K, Lupica CR. Altered Corticolimbic Control of the Nucleus Accumbens by Long-term Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Exposure. Biological psychiatry. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.07.024.

- Hancox, R. J., Shin, H. H., Gray, A. R., Poulton, R., & Sears, M. R. (2015). Effects of quitting cannabis on respiratory symptoms. The European respiratory journal, 46(1), 80–87. doi:10.1183/09031936.00228914

- https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/what-you-need-know-and-what-were-working-find-out-about-products-containing-cannabis-or-cannabis

- Crippa JA, Guimarães FS, Campos AC, Zuardi AW. Translational Investigation of the Therapeutic Potential of Cannabidiol (CBD): Toward a New Age. Frontiers in immunology. 2018;9. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02009.

Mile High Sports Magazine – Guest Article #3 – Oct. 2019

by Dr. Hy Gia Park and Dr. Charles Park

“I struggle more than people know… I remember sitting in my room for four or five days not wanting to be alive, not talking to anybody. That was a struggle for me.”

This is Michael Phelps, the most decorated Olympian of all time, describing his depression that led him to seek treatment. Athletes, even the most elite that appear superhuman, are not immune to the brain disease we call clinical depression. In fact, studies suggest that the annual occurrence of depression in athletes is similar if not higher than the general population rate of 6.7%.1 It has been estimated that 34% of current elite athletes have anxiety and depression and 26% in former elite athletes.2 In our two previous articles, we present the more updated theory regarding depression being a brain disorder that results from prolonged stress. Athletes experience a substantial amount of stress ranging from training, performance, winning, competition, physical injury, recovery, and retirement (see articles and public response to Andrew Luck). In fact, studies have identified more than 640 distinct stressors that could induce mental health symptoms and disorders during and after a professional or elite sport career. 2

Despite the clear data showing that athletes are susceptible to developing depression, there are numerous barriers to identifying and treating the disease in a timely manner. Stigma continues to be the biggest obstacle. For the athlete, there is fear about the implications regarding their athletic prowess and the subsequent consequences, such as loss of their sports career and financial security, should they disclose they are suffering from a mental health disorder. There is also the failure to understand what depression looks like; what is normal sadness versus true clinical depression. Furthermore, depression arises insidiously as opposed to a broken bone, which is more tangible and easier to identify. Larry Sanders summed it up best when he said, “It’s hard for people in my field to respect mental health. We say that the game is 90 percent mental, but yet mental health doesn’t get the respect of, like, an ACL [knee injury].” The good news is that mental health in elite sports is gaining more publicity in the last few years, whether it be headlines highlighting the tragic deaths of athletes from suicide or substance use or athletes like Michael Phelps and Larry Sanders who have come forward to share their stories. Their courage in showing their humanness is coming at a time when we have better treatments to address this debilitating medical condition.

Depression is a treatable condition, especially with new innovative technologies, like deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (dTMS). dTMS may be a good treatment option for athletes because it focally targets the brain’s prefrontal cortex (PFC), where it is believed that the dysfunction in neuro-chemical and neuro-circuitry of depression lie. Depression is not just someone feeling sad, it is a brain disease that impairs a person’s thinking. For the athlete where executive functions of the PFC like, planning, problem solving, reasoning, working memory (understanding the environment around them), mental flexibility and creativity, focus, and impulse control, is the distinguishing factor between a “good” versus an “elite” player, treating the impaired part of the brain that is debilitated by depression is literally, a make it or break it deal.3 Targeted treatment means fewer side effects that are typically experienced with antidepressant medications and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), such as weight gain, memory problems, abnormal movements, coordination problems, constipation/diarrhea, vision problems, dry mouth, and headaches. Olympic swimmer Allison Schmitt once said, “Being vulnerable is not weakness. It shows you are strong enough to know that life is sometimes hard for you to handle and you need support.” In next month’s article we will further explore the topic of treatments for depression; why it treatment important, which treatments are backed by scientific evidence and which may potentially be harmful.

References:

- Onate, J.; “Depression in Ultra-endurance Athletes, A Review and Recommendations;” Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2019;27:31–34.

- Gouttebarge V, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Gorczynski P, et al. Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;53:700-706.

- Sakamoto, S., Takeuchi, H., Ihara, N., Ligao, B., & Suzukawa, K. (2018). Possible requirement of executive functions for high performance in soccer. PloS one, 13(8), e0201871. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0201871

- Colorado Health Institute: https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/research/suicides-colorado-reach-all-time-high

- WHO: Statement 10 September. World Suicide Prevention Day 2008.

Mile High Sports Magazine – Guest Article #2 – Sept. 2019

by Dr. Hy Gia Park and Dr. Charles Park

“Why do athlete’s commit suicide?”

Rashaan Salaam (1994 Heisman Trophy winner), Rick Rypien, Kenny McKinley (former Broncos player), Terry Long, Kerry Catlin, Tyler Hilinski, Madison Holleran… These elite athletes didn’t just share achievement and excellence traits. These athletes all died by their own hands. September is National Suicide Awareness and Suicide Prevention Month. In our ongoing series about clinical depression, we will examine how this brain disease impairs cognitive functions, the most serious of which leads to suicide.

Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide and in the US. On any given day, over 2000 people die by suicide worldwide1; 129 of these occur across the US2 with 3 occurring specifically in Colorado.3 In nearly every state in the US, the suicide rate has increased by 25% from 1999 to 2016.4 Even more disturbing is that the World Health Organization estimates that for each adult who died by suicide there may have been more than 20 others attempting suicide.5 The significance of suicide to this ongoing exploration of the phenomenon called clinical depression is that two-thirds of individuals who commit suicide suffer from depression.6 As previously discussed in our August article, depression is more than just “sadness”, it is a chronic and debilitating neurological disease that should be treated like any other chronic disease like diabetes and heart disease.

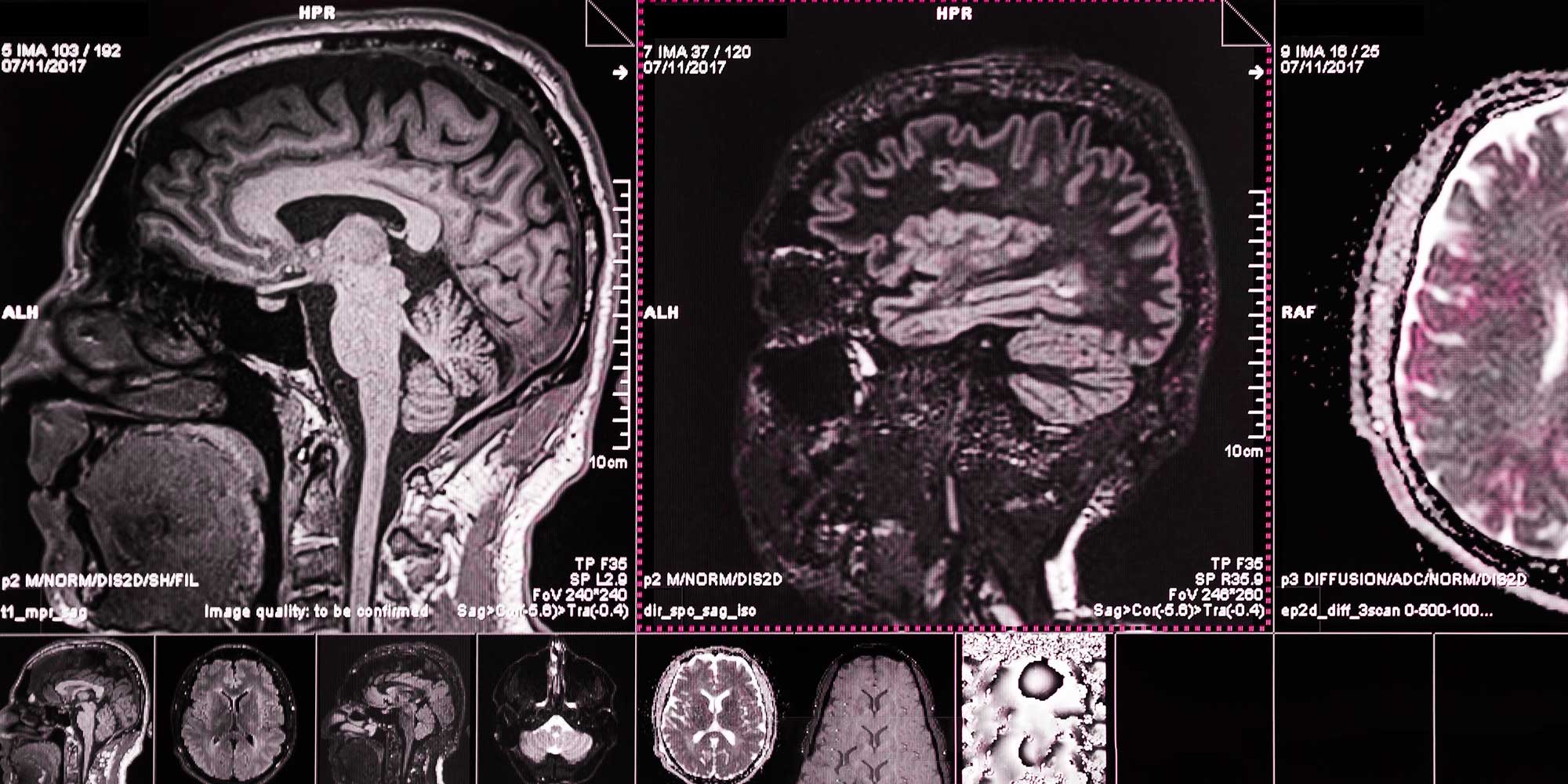

Oxford dictionary defines a disease as a disorder of structure or function in a human that produces specific symptoms. Clinical depression results from brain dysfunction where the brain is abnormally stuck in the fight or flight mode (a.k.a. “the stress response”). Depression has strong genetic and environmental influences (e.g. concussions), and these influences seem to prolong this abnormal stress response. The structural changes and dysfunction seen in depression occurs in the vital front parts of the brain called the prefrontal cortex (PFC).7 To review, the PFC is responsible for the brain functions collectively called executive functions (i.e. planning, decision-making, problem-solving, self-control/impulse control, personality expression and appropriate social behavior). Scientists who have examined individuals who have attempted and/or completed suicide, found that the PFC has atrophied in these individuals. Scientists have also found similar loss of size in the temporal lobes, which is responsible for short-term memories, attention, language abilities, mood, and visual perceptions (dysfunction can cause hallucinations). Collectively, dysfunction in these two areas lead to the irrational decision-making seen in patients who attempt suicide. Along with this dysfunction and atrophy in the PFC and temporal lobe, those with suicidal behaviors also showed an over-activity in another crucial part of the brain called the amygdala. This structure is part of the limbic system, which is responsible for processing memories and learned behaviors tied to fear and anxiety. Between the underactivity of the PFC and temporal lobes and hyperactivity of the amygdala and limbic system, this imbalance leads to an over-response to fear and negativity, and irrational and inaccurate self-reflection, impaired decision making, and loss of impulse control. Individuals with depression can appear more like they have early dementia than “just feeling sad.” They often experience memory and concentration problems, will describe being easily overwhelmed by even the simplest of choices, and rigidly stick to only irrationally negative views of themselves and life events.

Researchers have consistently identified three cognitive patterns in suicidal individuals:

- an irrational view that certain life events automatically signal defeat,

- irrational view that they cannot solve problems, and

- inability to anticipate future problems. These three deficiencies in thinking lead to the irrational hopelessness seen in depressed and suicidal patients.8 Armed with this more sophisticated understanding of clinical depression, scientists have developed exciting new treatments to tackle this disease.

Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (dTMS), an FDA-approved depression treatment available since 2013, uses strong painless magnetic fields that specifically target the PFC. The focal targeting of the magnetic pulses has the benefits of reducing side effects seen in older treatments like medications and ECT. Medications distribute throughout many parts of the brain and body, so it is not surprising that they cause systemic side effects such as weight gain, sexual dysfunction, nausea, tremors, dry mouth, diarrhea, headaches, constipation, sweating, and sleepiness. While ECT is slightly more targeted to the brain, it does come with its own risks. ECT exposes patients to anesthesia and muscle relaxants and involves the use of electric currents to induce brief seizures to reverse depression symptoms. dTMS is completely different – there is no need for anesthesia or muscle relaxants and no seizure is triggered, which means no risks and complications from anesthesia, no confusion, no memory problems, and the recovery period after dTMS takes a few minutes compared to several hours with ECT. With dTMS the patient remains awake during the 20-minute treatment and can return to work or other daily activities immediately after the procedure. But what makes dTMS treatment even more impressive is the speed in which patients report improvement. Anecdotally, our patients report signs of improvement in concentration, memory, energy, and motivation typically by session fifteen. “When you are depressed, your reality is too much to handle and your tolerance for life is low. The world feels like it is caving in on you and you feel all this pressure.” This was how a 22 year old Arahant patient, describes her experience with depression. After she completed the entire dTMS protocol of 36 sessions, she shared that:

“TMS helped to raise my tolerance for life. It made life feel brighter and easier. I was able to feel a sense of peace with things as they are as opposed to all of it being too scary or too much to handle. That pressure was no longer there.”

We want to spread the important message that depression is a treatable condition and dTMS is a tolerable and effective treatment that can help to improve PFC functioning. Improvement in the depressed individual’s ability to fully experience, accurately and realistically interpret, and to effectively respond to life events is an obvious treatment outcome when we think about the loss of impulse control and irrationality seen in patients struggling with thoughts of suicide. Improved impulse control and reduction in irrational thought processes might be the difference between acting on thoughts of suicide versus reaching out to loved ones and seeking help. This improvement in split second decision-making opens up other hypothetical scenarios with this technology. For example, could it improve the split-second decision-making abilities in athletes, another group of young people at risk for depression and anxiety disorders due to the pressures they face in the 21st century?

References:

- World Health Organization (WHO): https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml

- Colorado Health Institute: https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/research/suicides-colorado-reach-all-time-high

- United health Foundation: https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/Suicide/

- WHO: Statement 10 September. World Suicide Prevention Day 2008.

- NIMH: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/suicide-prevention/index.shtml

- Gold, P.W.; “The organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in depressive illness;” Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 32–47; doi:10.1038/mp.2014.163

- Desmyter, S., Van Heeringen, C., & Audenaert, K. (n.d.). Structural and functional neuroimaging studies of the suicidal brain. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry., 35(4), 796-808.

Mile High Sports Magazine – Guest Article #1 – Aug. 2019

by Dr. Hy Gia Park and Dr. Charles Park

“Can’t you just be happy?! Get over it! It’s only in your head.”

These are typical remarks that depressed individuals frequently hear. Implicit in these statements are: if you are depressed, you are not trying and feeling happy means you are better. These are all misconceptions and it is time to set the facts straight about clinical depression.

Emotions like happy and scared are sensory data about intrapsychic states resulting from interactions with others and the environment and should be used for navigating life, not goals for depression treatment. Rather than “being happy,” achieving remission from depression means stabilizing cognitive function so that the individual can once again, engage in meaningful relationships and hobbies, and feel a sense of life purpose. Individuals suffering from this medical condition need to be able to understand how to use these data sets to increase their capacity to love, play, and work, and this in turn, leads to the commonly desired treatment goals of happiness and contentment. Emotions provide the guidance needed to make ‘right’ choices and decisions throughout life; they are often the ‘fuel’ or “gut feelings” that impel us to act or not. They guide and organize a group of brain functions called executive functioning that allow humans to plan, problem solve, execute, and arguably the most important function, suppress impulsive and/or counter-productive behaviors that may interfere with achieving life goals. Many of these cognitive activities are regulated by the front part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The PFC is in constant back and forth communication with, regulates (as well as being regulated by) more ‘reptilian’ automatic parts of our brain, where the fight-or-flight survival response resides. Ironically, depression, may actually arise from this stress system working a little TOO well.

Depression affects 7.1% of adults in the United States and studies suggest that this is the same rate, if not higher in athletes.1

Theories about depression have evolved beyond serotonin levels. Newer theories suggest that depression is actually a survival response (albeit prolonged) arising from long-term exposure to stress(es).2 Before continuing this discussion of depression, we do need to agree on definition of certain terms. Homeostasis is defined as the body’s baseline chemical state that it fights to maintain. Stress can be defined as any internal and external stimuli that disrupt homoeostasis. When the brain’s homeostasis is challenged by stress be it internal (e.g. “will I make the team?”), interpersonal stress (e.g. relationships with coaches and teammates), chemical (e.g. drugs or alcohol) or environmental (e.g. playing on turf versus grass), this stress leads to a cascade release of certain brain chemicals.

Stable brain chemistry is required for the brain to function properly and minimize the symptoms of depression. For the purpose of this discussion, a normal homeostatic brain is akin to a heating/cooling system where the thermostat is set at a comfortable 68° F. Any form of stress will initially and temporarily push the thermostat or neurochemistry of the brain (e.g. serotonin, dopamine levels) out of whack. The programming of the brain has evolved over time to always maintain the thermostat setting at 68° F so it immediately responds to the change by releasing a series of chemicals to bring the thermostat setting back to normal. Stress chemicals such as, glutamate, norepinephrine, cortisol, and corticotropin releasing factor lead to either over-functioning or under-functioning of neurocircuits to illicit a rapid response to danger. Turning off PFC function and allowing more automated, primitive parts of the brain to respond to danger is more efficient. The problem in depression is that the brain is stuck in this mode even if we have successfully averted danger but now, the new thermostat setting has been re-set to 80° F, regardless of appropriateness. Prolonged over/under-functioning in these neurocircuits in response to this new thermostat setting causes the body’s fight-or-flight system to stay on longer than necessary and leads to dysfunction of thinking and behaviors, the phenomenon we call clinical depression.

Disability from depression comes from the body’s response to prolonged stress, which ultimately atrophies the PFC. This explains why depression is the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide and current epidemiological trends project that by 2020 it will become the second leading cause of disability worldwide.1 Individuals with depression lose their ability to correctly and rationally interpret and respond to sensory data. They will often say they are not sad but describe difficulty engaging in pleasurable activities – “I just work and sleep.” A sense of worthless or guilt completely out of proportion to the perceived sin is common and ultimately leads to the internal experience of hopelessness. Excessive fatigue, fogginess of memory and thinking, low motivation, appetite changes, sleep problems, poor concentration make the simplest of tasks appear overwhelmingly challenging. Effective depression treatment should address both the disruptions in the neuro-chemicals and the neuro-circuits.

Up until the last decade, the options for depression treatment have been limited to medications to treat the neurochemical disruptions and psychotherapy to address the dysfunction in the neurocircuits. Enter Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (dTMS), a novel medical procedure similar to Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). It is an emerging non-invasive brain stimulation technique that uses magnetic fields to stimulate brain cells without the need for medications or anesthesia. With dTMS, an electromagnetic coil placed adjacent to the scalp is used to apply brief magnetic pulses to the brain. The painless magnetic pulses modulate brain network activity in the region of your brain involved in mood regulation, depression, and anxiety. It’s like physical therapy for sports injuries. Focal targeting of the specific brain regions believed to be involved in depression leads to quicker improvements while avoiding systemic side effects common with antidepressant medications, such as fatigue, upset stomach, weight gain, and sexual dysfunction. Clinical studies have demonstrated dTMS’s effectiveness in normalizing PFC brain circuits and its general tolerability, which can be a game changer for the estimated 17.3 million adults in the United States who suffer from depression.3

At the end of the day, clinical depression is better seen from its cognitive dysfunction than whether or not the individual is “happy or sad.” It is the cognitive dysfunction that causes disability and hurts the individual and their loved ones. Furthermore, the irrationality that reflects the cognitive dysfunction is what creates the profound pain experienced with this illness. From the less extreme irrationality seen in the expressed thoughts and feelings of worthlessness, to the more concerning expressions of feeling trapped or hopeless, rapid treatment is necessary as the most profound expression of irrational hopelessness can be seen in the disease’s most dangerous symptom: thoughts and actions related to suicide.

Sources

- Gouttebarge V, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Gorczynski P, et al. Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2019;53:700-706.

- PW Gold; “The organization of the stress system and its dysregulation in depressive illness;” Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 32–47; doi:10.1038/mp.2014.163

- National Institute of Mental Health

Since this is our first blog post, we would like to introduce ourselves. This blog will be written by a 9th grader, a 7th grader, and a 4th grader, who is also our youngest writer. We are siblings who have two board-certified psychiatrists as parents.

To start off with our oldest writer’s opinion:

I wanted to write this blog because so many kids that I go to school with have depression, anxiety, or ADHD and they don’t know how to talk about it with their parents. Instead of going to adults, they go to their friends who also don’t know how to deal with it. Many of my friends also come to me for help as they mostly have depression and do things like self-harm and don’t want to talk with anyone because it will become “too much of a big deal.” So with this blog I hope to not only help my friends but many other teens and children who have trouble with their mental health.

The view of the youngest:

I wanted to help with this blog because I have anxiety and it becomes really bad when I go to bed at night. I have fears of being hurt at night and even fears of people judging what I wrote in this blog. I couldn’t talk about my anxiety with my friends or parents because my anxiety told me that If I told my friends I would be dragging them with me into anxiety. I told myself that my parents wouldn’t listen or care if I told them about my anxiety. I have a little depression and I just hated having feelings because I never knew how to talk about my feelings or being asked if I was ok. I would cry.

Lastly, a middle child’s opinion:

I wanted to contribute to this blog considering I am a child that has problems with anxiety and depression daily and how much of a struggle it is. Many of my friends struggle with anxiety and other issues in their families. Despite the problems of mental illness, hearing about my parents’ work with patients gives me a different feeling about mental wellness. With more kids and adults with mental sickness it is nice to see that there are psychiatrists willing to treat these illnesses.